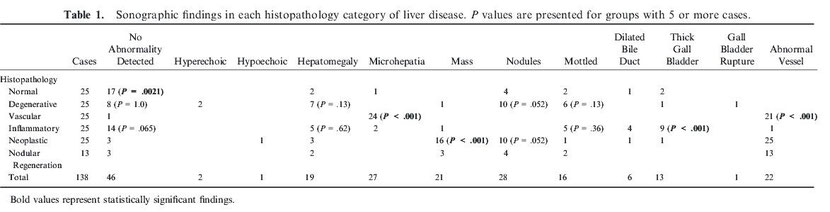

Results

The inclusion criteria were met by the records of 138 cases (Table 1). The histopathologic diagnoses included normal (n = 25), degenerative (n = 25), vascular

(n = 25), inflammatory (n = 25), neoplastic (n = 25), and nodular regeneration (n = 13). The method of acquisition of liver tissue included surgical

(n = 81), necropsy (n = 29), tru-cut needle (n = 22), and clamshell laparoscopic (n = 5) biopsy.

There was a significant association between a normal ultrasound examination (no abnormality detected) and normal histopathology (P = .0021). Of dogs with no abnormality

detected on hepatic ultrasound exam, 17 (37%; 0.23–0.52) had normal histopathology results. However, 29 (63%; 0.48–0.77) of the sonographically unremarkable livers had histopathologic

abnormalities, including inflammatory (14), degenerative (8), neoplastic (3), nodular regeneration (3), and vascular (1) diagnoses (Table 1). In contrast, 8 dogs had normal

histopathology, but an abnormal ultrasound examination, including nodules (4), hepatomegaly (2), mottled (2), microhepatia (1), thickened gallbladder wall (2), and dilated common bile duct

(1).

No sonographic findings were significantly associated with a histologic diagnosis of degenerative disease, but sonographic identification of nodules approached significance

(P = .052). Dogs with a histopathologic diagnosis of degenerative disease had sonographic abnormalities identified in 17 (68%; 0.47–0.85), including nodules (10),

hepatomegaly (7), mottled parenchyma (6), hyperechoic parenchyma (2), mass (1), thickened gallbladder wall (1), and gallbladder rupture (1). Of the 25 degenerative disease cases, 8 (36%;

15–54%) had no abnormality detected on ultrasound examination.

Both microhepatia (P < .001) and the identification of abnormal vasculature (P < .001) were independently associated with a histopathologic

diagnosis of vascular disease. Dogs with a histologic diagnosis of vascular disease had sonographic findings of microhepatia and abnormal vasculature identified in 96% (0.80–1.0) and 84%

(0.64–0.95) of cases, respectively. Of the 25 cases with vascular histopathology, 21 had a single congenital portosystemic shunt confirmed at surgery. Twenty (95%; 0.76–1.0) of the congenital

portosystemic shunts were identified sonographically. Of the remaining dogs, 2 had multiple acquired shunts confirmed at surgery and 2 had vascular lesions without shunting diagnosed by

transplenic portal scintigraphy using Tc99m pertechnetate. Both of the cases with acquired shunts were diagnosed with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

The inflammatory hepatopathy category, when evaluated as a whole, had 14 (56%; 0.35–0.76) cases without any abnormality detected on ultrasound examination. The abnormalities detected in the

remaining cases included thickened gallbladder wall (9), mottled (5), hepatomegaly (5), dilated common bile duct (4), microhepatia (2), and mass (1). The inflammatory hepatopathy group then

was subdivided into specific diagnoses of reactive hepatitis, acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, and cholangiohepatitis (Table 2). A sonographically normal-appearing hepatic parenchyma

was the most common finding in the chronic hepatitis group (57%; 0.29–0.82) and the second most common finding in the cholangiohepatitis group (63%; 0.25–0.91). Both dilated common bile duct

(50%; 0.16–0.84) and thickened gall bladder (88%; 0.47–1.0) were commonly seen in cases of cholangiohepatitis, and sonographic identification of a thickened gall bladder wall was

significantly associated with inflammatory histopathology (P < .001). Of the 4 dogs with both dilated common bile duct and thickened gall bladder, histopathology

indicated cholangiohepatitis in 3.[25] Histopathology was normal in the single dog that was diagnosed with a gall bladder mucocele on ultrasound examination.

The 25 cases of hepatic neoplasia included hemangiosarcoma (8), hepatocellular carcinoma (8), lymphoma (2), metastatic carcinoma (2), biliary carcinoma (1), neuroendocrine carcinoma (1),

fibrosarcoma (1), sarcoma (1), and mast call tumor (1) (Table 3). Ultrasound examination frequently identified sonographic abnormalities in livers with neoplasia. Only 3 of 25 (12%;

0.026–0.31) livers with neoplasia were sonographically normal. The identification of a hepatic mass was significantly associated with a diagnosis of neoplasia (P < .001) and

was present in 16 (64%; 0.43–0.82) cases. Of the 9 dogs with neoplasia that did not have a mass identified on ultrasound examination, 5 had nodules identified. Three of these 5 dogs had multiple

nodules. The 3 sonographically unremarkable livers with neoplasia had metastatic hemangiosarcoma (1), lymphoma (1), and metastatic carcinoma (1).

Of the 21 livers with masses identified on ultrasound examination, 76% (0.53–0.92) had neoplasia identified on histopathology. The histopathologic findings in the 5 dogs with nonneoplastic

masses included nodular regeneration (3), degenerative (1), and inflammatory (1). The liver biopsy samples in these cases were collected surgically (3), by ultrasound-guided biopsy (1), and

at necropsy (1).

No sonographic findings were significantly associated with any extent of fibrosis. Thirty-three (24%; 0.17–0.32) dogs had some degree of fibrosis identified on histopathology (Table 4).

Of the 47 dogs in this study that had sonographically unremarkable livers, 19 (40%; 0.26–0.56) had some degree of fibrosis. Fibrosis scores in these sonographically unremarkable livers ranged

from 1 to 4. The histopathologic abnormalities detected in the 11 cases with a fibrosis score of 3 or 4 included chronic hepatitis (4), cholangiohepatitis (3), nodular regeneration (2),

degenerative (1), and hepatocellular carcinoma (1). Four dogs had grade 4 fibrosis (cirrhosis), and there was no sonographic finding significantly associated with severe fibrosis.

Discussion

Similar to other reports,[5, 6, 26, 27] this study confirmed the accuracy of ultrasound examination for identification of portosystemic vascular shunts. The liver was considered small in 96%

of dogs with primary vascular disease, and in 100% of dogs with macrovascular portosystemic shunts. Although all but 1 dog with a portosystemic shunt in this study was accurately identified

on abdominal ultrasound examination, another dog with acquired multiple portosystemic shunts secondary to primary portal vein hypoplasia was classified as a congenital shunt. This

misclassification is not surprising given that the reported sensitivity for sonographic identification of multiple acquired portosystemic shunts is low (67%) compared with that of congenital

shunts (90–100%).[6]

Ultrasound examination identified abnormalities in 88% of livers with neoplastic disease, and sonographic identification of a mass was significantly associated with neoplasia. Although this

demonstrates that hepatic ultrasonography is useful for the identification of hepatic neoplasia, 5 dogs with hepatic masses were found to have a variety of other diagnoses, primarily

degeneration, inflammation, or nodular hyperplasia. Assuming that the histopathologic diagnosis was correct, our findings confirm that whereas the presence of a hepatic mass may raise concern

for neoplasia, the diagnosis must be confirmed with histopathology. However, had our study recorded all sonographic examination abnormalities rather than just hepatic changes, the accuracy of

diagnosing neoplasia may have improved. This is supported by findings of a recent study that reported that dogs with large liver masses and peritoneal effusion on ultrasound examination were

most likely to have malignant hepatic neoplasia.[28] In addition, there is substantial variability in the expected sonographic appearance of diffuse versus focal hepatic neoplasms. For

example, hepatocelluar carcinomas frequently produce mass lesions, whereas diffuse diseases such as lymphoma can have more variable sonographic findings[14]. We were unable to draw

conclusions regarding the variability in these diffuse patterns, because the majority of neoplastic livers reported here contained either nodules or mass lesions.

Nodular hyperplasia can result in a mass that is consistent with the ultrasound findings in the nonneoplastic masses reported in this study, and often degenerative changes are noted on

histopathology of this abnormality.[15, 20] Alternatively, biopsies in these cases may not have been representative of the bulk of the mass and may not have include neoplastic tissue. Many

primary hepatocellular neoplasms are well differentiated, with hyperplasia, adenoma, and even sometimes carcinoma being difficult to differentiate, particularly in small samples. Degenerative

changes, including reticulated cytoplasm with a vacuolar appearance, can be present in nodular hyperplasia and primary hepatocellular neoplasia as well. Although it is possible that a

neoplasm might have been diagnosed if additional tissue had been obtained, biopsies were collected surgically or at necropsy in 4 of these 5 cases.

An unremarkable ultrasound examination was significantly associated with normal histopathology (P = .0021), but 63% of cases in this category had abnormalities on

histopathology. The inflammatory group made up nearly half of these cases. This finding is similar to other studies in which ultrasound examination frequently is normal in dogs with

inflammatory hepatopathies.[20, 29, 30] An unremarkable ultrasonographic appearance of the liver also was common in dogs with degenerative lesions, similar to other reports.[29] These

findings suggest that there are considerable limitations in the sonographic identification of diffuse liver diseases such as inflammatory or degenerative disease. Degenerative disease, in

particular, had a wide variety of ultrasound abnormalities, and no specific pattern of findings was predictive of degenerative histopathology. Therefore, these findings demonstrate the

variable appearance of this category.

Cholecystitis and gall bladder mucocele are commonly associated with cholangitis and cholangiohepatitis,[30-32] likely accounting for the frequent identification of biliary inflammation in

cases with dilated common bile duct or thickened gall bladder wall. In addition, sonographic identification of a thickened gallbladder wall was significantly associated with inflammatory

histopathology (P < .001). This finding is similar to that reported by Guillot et al, where 9/15 dogs with inflammation on fine-needle aspiration cytology of the

liver had an abnormal appearance of the biliary system on ultrasound examination.[33] However, because the results of hepatic cytology may not be comparable to hepatic histopathology,

additional work is needed to better define the relationship between sonographic biliary abnormalities and hepatic parenchymal histopathologic findings. Furthermore, the canine biliary tract

may remain dilated after resolution of a previous insult[25]; therefore, biliary dilatation is not always indicative of active biliary disease.

Eight cases with normal histopathology had ≥1 abnormalities identified on ultrasound examination. The finding of normal histopathology in these cases raises concern for whether the biopsy

sample may not have been representative of the actual underlying disease. However, in 5 of these 8 cases, samples had been collected surgically and were of high quality. The remaining 3 were

collected by needle biopsy and were considered adequate for interpretation by the pathologist. This would suggest that not all sonographic abnormalities are truly associated with underlying

hepatic pathology and reinforces the importance of considering all factors in a case before pursuing biopsy of the liver.

There were no sonographic features significantly associated with detectable hepatic fibrosis, and in many cases, substantial fibrosis produced no sonographic abnormalities. Forty-one percent

of sonographically normal livers in this study had some degree of fibrosis ranging from mild to severe. Of the cases with a fibrosis score of 3 or 4, sonographic abnormalities were identified

inconsistently. Ultrasound examination cannot reliably be used to detect or predict the presence or absence of or the degree of hepatic fibrosis.

Some limitations of this study include reliance on the opinion of a single pathologist as the gold standard for diagnosis of hepatic pathology and a single radiologist for interpretation of

ultrasound examinations. Use of a single ultrasonographer likely resulted in more consistency in findings among cases compared with multiple observers.[13] However, this introduces bias

toward the individual's interpretation that may be different from that of other ultrasonographers. For example, the low prevalence of generalized changes in echogenicity in our population

might be the result of such bias. Furthermore, although some sonographic videos were available for review, the use of still sonographic images may have limited complete interpretation.

Standardized criteria for histopathologic and ultrasonographic findings were employed in this study in an attempt to minimize any bias. In addition, it was assumed that the biopsy specimen

was representative of the actual hepatic disease. This may not have been accurate in cases of focal disease if the biopsy was taken from adjacent tissue. Furthermore, some livers contain

multiple histopathologic abnormalities that require multiple biopsies for diagnosis.[34] Small or poor quality samples may have affected the accuracy of histopathology,[35] although most

samples in this study were obtained at surgery or necropsy and all were judged adequate for histopathologic interpretation by the pathologist. It should be recognized that surgical and needle

samples may be obtained for different reasons. For example, a surgical sample may be collected from a grossly or palpable abnormal area of the liver, whereas needle biopsies may target

sonographically abnormal areas. Although ultrasound-guided needle biopsies may have the advantage of sampling deep lesions not grossly visible at the hepatic surface, the small sample size

may lead to inaccurate histopathologic interpretation.[35] In this study, a mass was defined as a focal hyperechoic or hypoechoic area >3 cm in diameter. This measurement was chosen

because a previous study demonstrated that hepatic masses >3 cm are likely to be neoplastic.[28] However, the measurement chosen to classify a hepatic nodule or a mass was arbitrary.

Future studies should determine the measurement that would best differentiate neoplasia and benign disease.

Small numbers of liver samples with nodular regeneration or grade 4 fibrosis (cirrhosis) limited the ability to draw conclusions about these groups. Significant associations may have been

identified if a larger sample had been obtained. An additional limitation of the study was the use of hematoxylin and eosin as the only stain on histopathologic evaluation. Stains

specifically identifying fibrosis likely would have increased the sensitivity of the evaluation of fibrosis. Although the authors feel that substantial fibrosis would be identified by the

stain utilized and the use of the grading system, additional study is indicated to more definitively explore any association of ultrasonographic abnormalities with fibrosis. Although hepatic

sonographic abnormalities, including microhepatia, are significantly associated with histopathology, many sonographic changes are inconsistent and unable to accurately predict underlying

disease.

These limitations of hepatic ultrasonography should be acknowledged when using hepatic ultrasound examination in the diagnosis of canine liver disease.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest: Authors disclose no conflict of interest.

The study was completed without grant funding.

The material has not been previously presented.

Footnote

Share this article / Teilen Sie diesen Artikel