Article added / Artikel hinzugefügt 01.10.2021

Generally Articles and Discussions about Osteosarcoma in Dogs

→ Evaluations of phylogenetic proximity in a group of 67 dogs with

osteosarcoma: a pilot study

Article added / Artikel hinzugefügt 01.10.2021

Generally Articles and Discussions about Osteosarcoma in Dogs

→ Canine Periosteal Osteosarcoma

Images added / Abbildungen hinzugefügt 02.05.2019

Generally Sonography Atlas of Dogs →

Cardiovascular system → Pulmonary vessels

New subcategory added / Neue Unterkategorie hinzugefügt 02.05.2019

Generally Sonography Atlas of Dogs →

Cardiovascular system → Pulmonary vessels

Images added / Abbildungen hinzugefügt 01.05.2019

Generally Sonography Atlas of Dogs →

Cardiovascular system → Heart valvular diseases

AAHA Oncology Guidelines for Dogs and Cats

Barb Biller, DVM, PhD, DACVIM (oncology), John Berg, DVM, MS, DACVS, Laura Garrett, DVM, DACVIM (oncology), David Ruslander, DVM, DACVIM (oncology), DACVR, Richard Wearing, DVM, DABVP,

Bonnie Abbott, DVM, Mithun Patel, PharmD, Diana Smith, BS, CVT, Christine Bryan, DVM "AAHA Oncology Guidelines for Dogs and

Cats"

Abstract

All companion animal practices will be presented with oncology cases on a regular basis, making diagnosis and treatment of cancer an essential part of comprehensive primary care. Because each oncology case is medically unique, these guidelines recommend a patient-specific approach consisting of the following components: diagnosis, staging, therapeutic intervention, provisions for patient and personnel safety in handling chemotherapy agents, referral to an oncology specialty practice when appropriate, and a strong emphasis on client support. Determination of tumor type by histologic examination of a biopsy sample should be the basis for all subsequent steps in oncology case management. Diagnostic staging determines the extent of local disease and presence or absence of regional or distant metastasis. The choice of therapeutic modalities is based on tumor type, histologic grade, and stage, and may include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and adjunctive therapies, such as nutritional support and pain management. These guidelines discuss the strict safety precautions that should be observed in handling chemotherapy agents, which are now commonly used in veterinary oncology. Because cancer is often a disease of older pets, the time of life when the pet–owner relationship is usually strongest, a satisfying outcome for all parties involved is highly dependent on good communication between the entire healthcare team and the client, particularly when death or euthanasia of the patient is being considered. These guidelines include comprehensive tables of common canine and feline cancers as a resource for case management and a sample case history. (J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2016; 52:181–204. DOI 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6570)

Introduction

Every primary-care companion animal practice will encounter its share of oncology cases. This has never been truer since improvements in pet nutrition, widespread heartworm control, renewed emphasis on age-specific preventive pet healthcare, regular vaccinations, and senior pet screenings have led to a growing population of older dogs and cats. In fact, a large-scale (n > 74,000 dogs), two-decade demographic study of the Veterinary Medical Database found that neoplastic disease was the most common terminal pathological process in 73 of 82 canine breeds and the most common cause of death in dogs >1 yr of age, with an incidence >3 times that of traumatic injury.1 Because oncology cases are inevitable in clinical practice, some degree of expertise in diagnosis and treatment of cancer is expected by clients and is an essential component of a comprehensive primary-care veterinary practice.

The purpose of these guidelines is to provide practice teams with guidance for accurate diagnosis and optimal management of the canine and feline cancer patient. Because almost all pet owners have some acquaintance with cancer in their own lives, they will measure a veterinarian’s approach to managing an oncology case against their own experience. Perhaps to a greater degree than in other clinical situations, the client plays a prominent role in directing how a pet’s cancer is managed. For this reason, it is particularly important that veterinarians adopt an informed and systematic approach to managing an oncology case, including maintaining an active and empathetic dialogue with the owner in developing a treatment plan.

Every cancer case is different, even if the type of neoplasia is commonplace. For this reason, these guidelines are specific in many respects without being overly prescriptive. Within this framework, these guidelines offer the following sequential approach to managing each medically unique cancer case: diagnosis, staging, therapeutic considerations, careful attention to patient and personnel safety in handling chemotherapeutic agents, referral to an oncology specialty practice when appropriate, and a strong emphasis on client support.

Because oncology patients are frequently of an advanced age, their owners are often highly bonded to them and emotionally distraught after receiving a cancer diagnosis. Thus, a team approach emphasizing compassionate and transparent communication from clinical staff to pet owner and, in difficult cases, involving a referral center are critical factors in a satisfactory case outcome. A later section of these guidelines discusses in detail the importance of maintaining an empathetic, informed dialogue with the client, including techniques for discussing the patient’s prognosis and treatment options.

Because oncology cases have the potential to create a strong bond between the practice and the owner of a pet with cancer, primary-care veterinarians should be willing to consider treating select cases. The caveat in doing so is to ensure that the healthcare team is adequately trained and equipped to appropriately manage the case. A section on safety discusses in detail the safety precautions and equipment that are appropriate when chemotherapeutic agents are used. These include the equipment needed and methods used to protect the clinic environment as well as the healthcare team, the patient, and the pet owner.

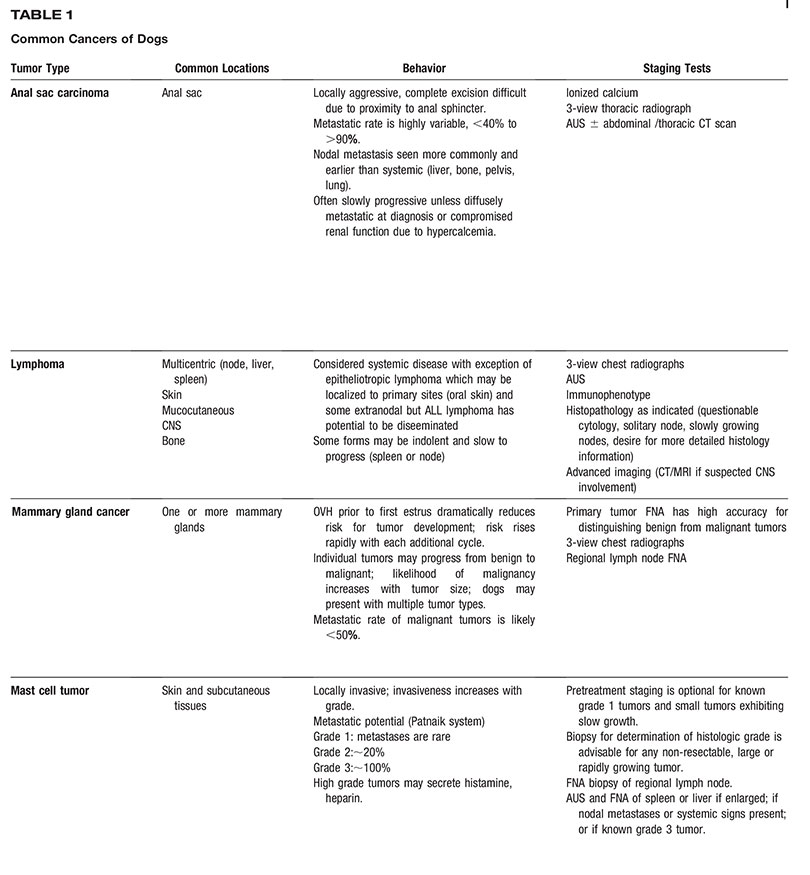

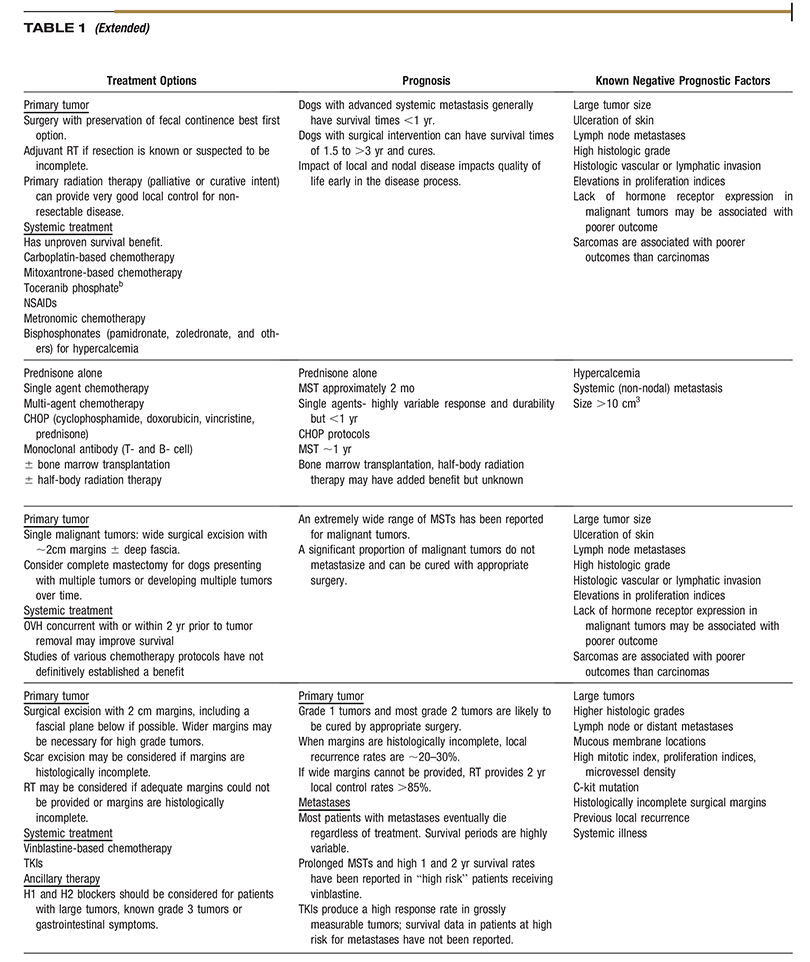

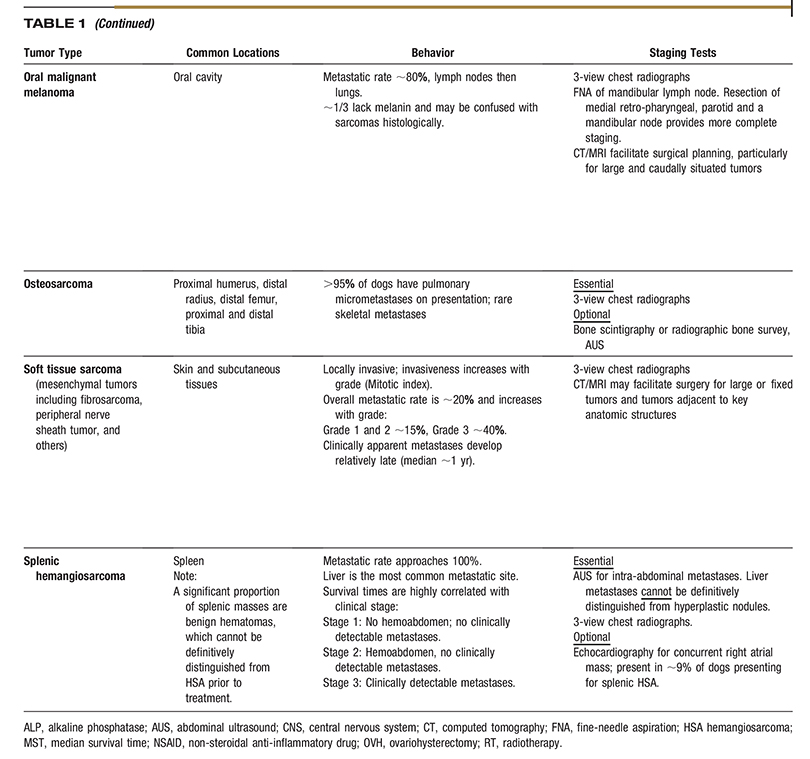

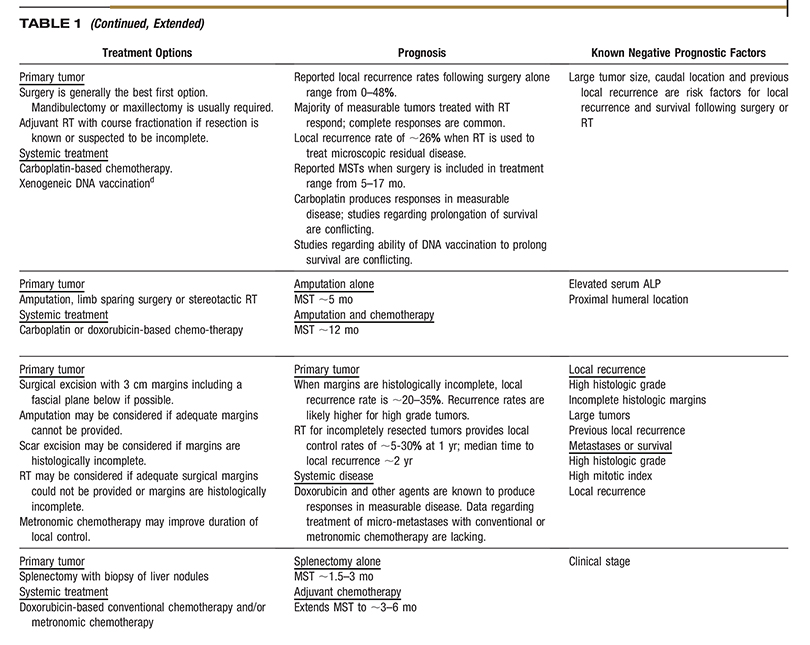

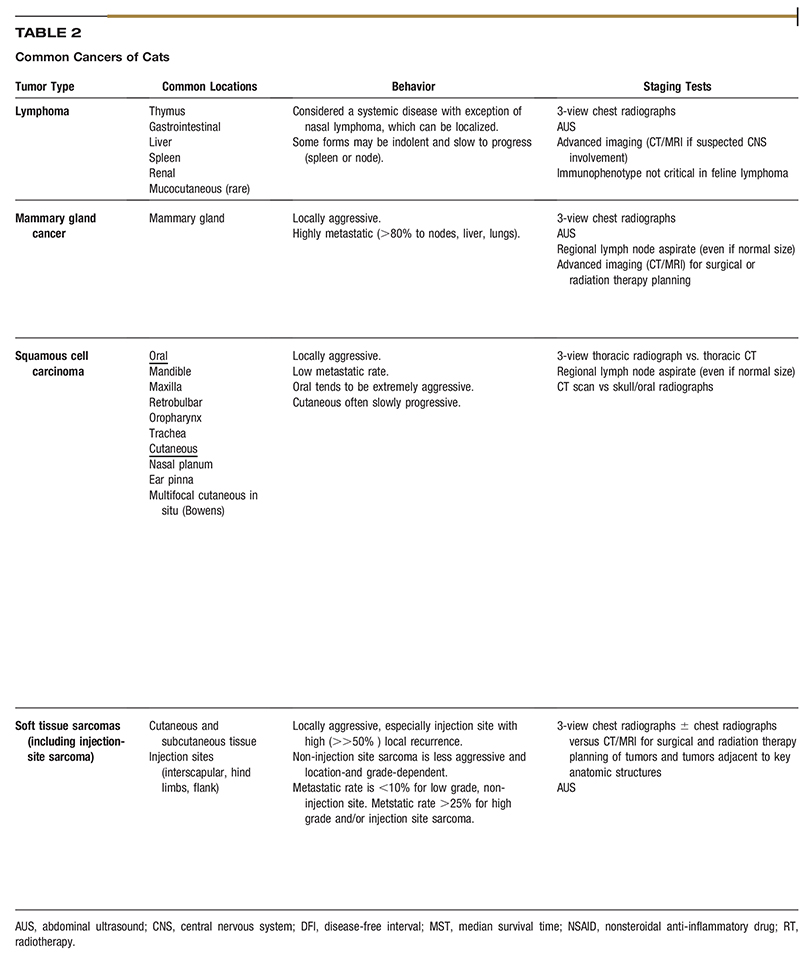

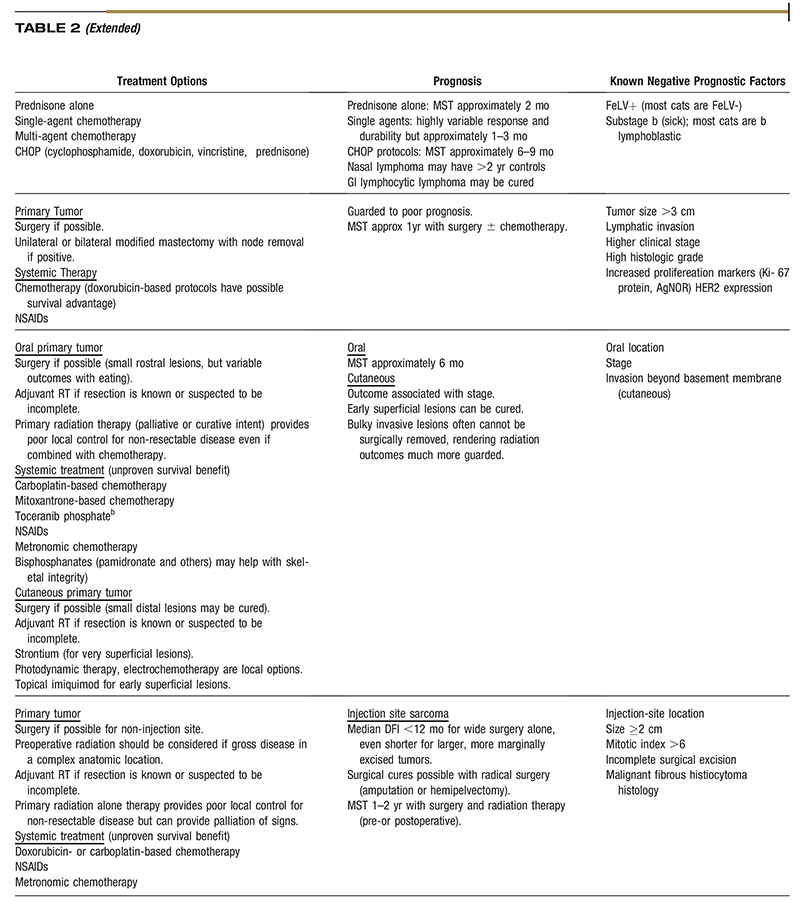

Each type of cancer and organ system involved has a particular progression to be considered when staging the case and presenting treatment options to the pet owner. A critical aspect of successful oncology case outcome is to develop a treatment plan specific for the type of tumor involved. Readers will find the two comprehensive tables on common cancers of dogs and cats to be a concise and useful resource for this purpose. The task force wishes to emphasize that the information in the tables should not be interpreted as a “cookbook approach” to case management but rather a compilation of relevant, tumor-specific information to help guide decision making. A sample case history is also provided so that practitioners can consider how they would use the cancer tables to assess and treat the case.

These guidelines are not intended to be overly prescriptive, for example, they do not provide chemotherapeutic dosage recommendations. Other, more complete sources of information are available for such purposes. However, these guidelines do place special emphasis on three topics of paramount importance in oncology case management: safety in handling chemotherapeutic agents, delivery of radiation therapy, and relationships with the owners of cancer patients.

As in all aspects of clinical veterinary medicine, each member of the healthcare team represents the practice as a whole. An underlying theme of these guidelines is that all staff members, including clinical and administrative personnel, can positively influence the outcome of an oncology case. A unified healthcare team that speaks with one voice will actively support a long-term relationship with a client who entrusts the practice with the care of a pet diagnosed with cancer.

Making a Referral and Working with Specialists

Practitioners who refer an oncology patient to a specialist should be mindful of the following considerations:

- Each patient and case is unique.

- Referral of an oncology patient is a multifactorial process that considers the patient’s quality of life (pre- and postreferral) and the pet owner’s preferences, emotional attachment to the animal, and the adequacy of his or her physical and financial resources to properly care for the animal.

- The primary care clinician, specialist, and pet owner must work together as a unified healthcare team and have a shared understanding of the options, procedures, and expectations of referral treatment.

- Aside from maximizing the patient’s survival, all parties involved in referral decisions should focus on the patient’s quality of life and the importance of providing compassionate, empathetic support for the owner.

Referral of an oncology patient may be appropriate for a variety of reasons. These include when the primary care veterinarian or the client wishes to consider all possible treatment options or when the referring veterinarian cannot provide optimum treatment for any reason. In addition, specialty referral practices often have access to clinical trials in which the client may want to participate.

Referral to a specialist should be case-specific. Referrals are appropriate when the primary care clinician can no longer meet the needs and expectations of the patient and client. The comfort level of the primary clinician and client with referral treatment will dictate how early in the process case transfer should occur. The importance of a clear, shared understanding of the referral process by the pet owner, primary care veterinarian, and specific referral specialists or referral centers cannot be overemphasized.

Determination of the preferred method of collaboration and case transfer between the primary care clinician and specialist should be made in advance of the referral treatment. It is also important to recognize that a variety of specialists may be needed at varying time points in the patient’s referral treatment process. After referral, it is important to establish a treatment plan for ongoing communication and continuity of care between the primary care clinician, the specialist, and the owner.

Diagnosis of Tumor Type

Cytology provides information based on the microscopic appearance of individual cells. Fine-needle sampling, which may or may not involve aspiration, can be performed safely for themajority of external tumors, without sedation or anesthesia. When performing fine-needle sampling, aspiration is useful when the tissue is firm and may be of mesenchymal origin, but collecting samples without aspiration can often result inmore diagnostic samples and lead to less blood contamination for soft tissue masses of round cell origin. Internal tumors can be sampled with ultrasound guidance depending on location, ultrasound appearance, and size. Cytology can often provide a definitive diagnosis of round cell tumors, and can be helpful in categorizing other tumors as mesenchymal or epithelial. With training and experience, the general practitioner can often determine the presence and type of neoplasia in the office. Submission to a clinical pathologist for diagnostic confirmation is usually indicated prior to therapy. Cytology does not provide tumor grade information and may not always provide a clear-cut diagnostic result due to poor sampling technique or the tumor type.

Cytology provides information based on the microscopic appearance of individual cells. Fine-needle sampling, which may or may not involve aspiration, can be performed safely for themajority of external tumors, without sedation or anesthesia. When performing fine-needle sampling, aspiration is useful when the tissue is firm and may be of mesenchymal origin, but collecting samples without aspiration can often result inmore diagnostic samples and lead to less blood contamination for soft tissue masses of round cell origin. Internal tumors can be sampled with ultrasound guidance depending on location, ultrasound appearance, and size. Cytology can often provide a definitive diagnosis of round cell tumors, and can be helpful in categorizing other tumors as mesenchymal or epithelial. With training and experience, the general practitioner can often determine the presence and type of neoplasia in the office. Submission to a clinical pathologist for diagnostic confirmation is usually indicated prior to therapy. Cytology does not provide tumor grade information and may not always provide a clear-cut diagnostic result due to poor sampling technique or the tumor type.

The goal of histopathology is to provide a definitive diagnosis when unobtainable by cytology. Histopathology provides information on tissue structure, architectural relationships, and tumor grade—results that are not possible with cytology. The histologic tumor grade may guide the choice of treatment and provide prognostic information. Proper technique is critical when performing a surgical biopsy, particularly to obtain an adequate diagnostic sample and to prevent seeding of the cancer in adjacent normal tissues.

Basic biopsy principles include the following:

- Obtain multiple samples from multiple locations within the tumor.

- Biopsy deeply enough to penetrate any overlying normal or reactive tissue.

- Handle biopsy specimens gently.

- Place samples in an adequate amount of formalin (10 parts formalin to 1 part tissue).

- To avoid seeding adjacent normal tissue with cancer cells, place the biopsy incision so that it can easily be excised at the time of definitive tumor removal.

- Excisional biopsy (i.e., removal of a tumor without prior knowledge of the tumor’s histologic type) may be appropriate if (1) principles of appropriate surgical excision of tumors are followed; and (2) staging procedures that might influence the owner’s decision to have an excision performed have been completed.

Ancillary tests can provide or confirm a diagnosis when routine histopathology does not yield definitive results. Tests such as immunohistochemistry, proliferation markers, special tissue stains, polymerase chain reaction, polymerase chain reaction for antigen receptor rearrangement (in this case for lymphoma), and flow cytometry can provide additional prognostic information or identify potential therapeutic targets. Communication with a pathologist or oncology specialist can be useful for identifying which ancillary tests may be indicated, how to perform them, and how they might be beneficial. Knowledge of the lymphocyte phenotype sometimes affects the treatment choice. For example, identification of a T-cell phenotype lymphoma generally indicates a poor or guarded prognosis, making the patient a candidate for any of several therapies that may differ from those typically used for a B-cell lymphoma. Immunohistochemistry, polymerase chain reaction for antigen receptor rearrangement, and flow cytometry can all be used to determine if a patient with enlarged lymph nodes has lymphoma versus a reactive process when an ambiguous cytology or histopathology report is obtained. However, which test to choose depends on the individual case.

Diagnostic Staging

Diagnostic staging is a mainstay of oncology case management. Staging is the process of determining the extent of local disease and the presence or absence of regional or distant metastasis. A thorough evaluation of the patient begins with a comprehensive physical exam and a minimum database, which includes a complete blood count, chemistry panel, and urinalysis. The scope of the diagnostic workup for staging purposes is dependent upon the known behavior of the individual tumor type combined with the owner’s goals, limitations, and expectations for therapy.

Evaluation of local disease starts with the physical exam to determine the size, appearance, and mobility or fixation of the primary tumor to adjacent tissues. If the neoplasia is internal, imaging via ultrasound, radiographs, computed tomography (CT), or MRI may be necessary for assessment of local extent of disease.

Regional tumor assessment involves evaluation of associated lymph nodes. Documentation of metastases to lymph nodes cannot reliably be made by palpation for size and other physical parameters, but requires cytology or histopathology. Because lymph node drainage can be highly variable, sampling of multiple nodes may be necessary for adequate staging. If a lymph node aspirate is non-diagnostic or if the lymph node cannot be accessed for aspiration, it is a candidate for excisional biopsy. For internal lymph nodes, imaging to assess and potentially guide aspiration is recommended. Imaging techniques useful in the detection of abnormal lymph nodesmay include thoracic radiographs, CT, and abdominal ultrasound.

Distant metastasis refers to spread of cancer beyond regional lymph nodes to distant organs. The presence of confirmed metastases generally implies a worse prognosis and may drastically affect therapeutic decisions. Complete staging can vary depending on the particular tumor type, but distant metastasis may be revealed by a thorough physical examination, abdominal and threeview thoracic radiographs, abdominal ultrasound, nuclear scintigraphy, bone scan, CT, positron emission tomography-CT, or MRI.

Therapeutic Modalities

Perhaps no disease entity is more dependent on a multimodal therapeutic approach than cancer. Understanding how these various therapeutic modalities complement each other in an integrated treatment plan is an essential aspect of successful oncology case management. For example, knowing when to initiate multiple treatment options concurrently or sequentially is important for therapeutic efficacy and ensuring the patient’s safety.

Therapeutic Modalities: Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy

Chemotherapy is now a commonly used treatment modality in veterinary cancer medicine. Conventional chemotherapy, metronomic chemotherapy, and targeted chemotherapy using tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are all currently available to the small animal practitioner and differ in their indications and goals. Therefore, in order to be successfully used in practice, the clinician must be aware of some of the basic principles of each approach. Knowledge of the appropriate administration techniques and potential side effects of the drugs to be used is also essential and will be covered in later sections.

General Principles of Conventional Chemotherapy

Conventional chemotherapy is also known as maximally tolerated dose (MTD) chemotherapy. This refers to administration of chemotherapeutic agents at the maximum recommended dose followed by a recovery period for drug-sensitive cells, such as those of the bone marrow and gastrointestinal tract. Although this approach maximizes tumor cell death and is associated with a low chance of serious side effects, the periods between treatments may also allow for tumor regrowth.

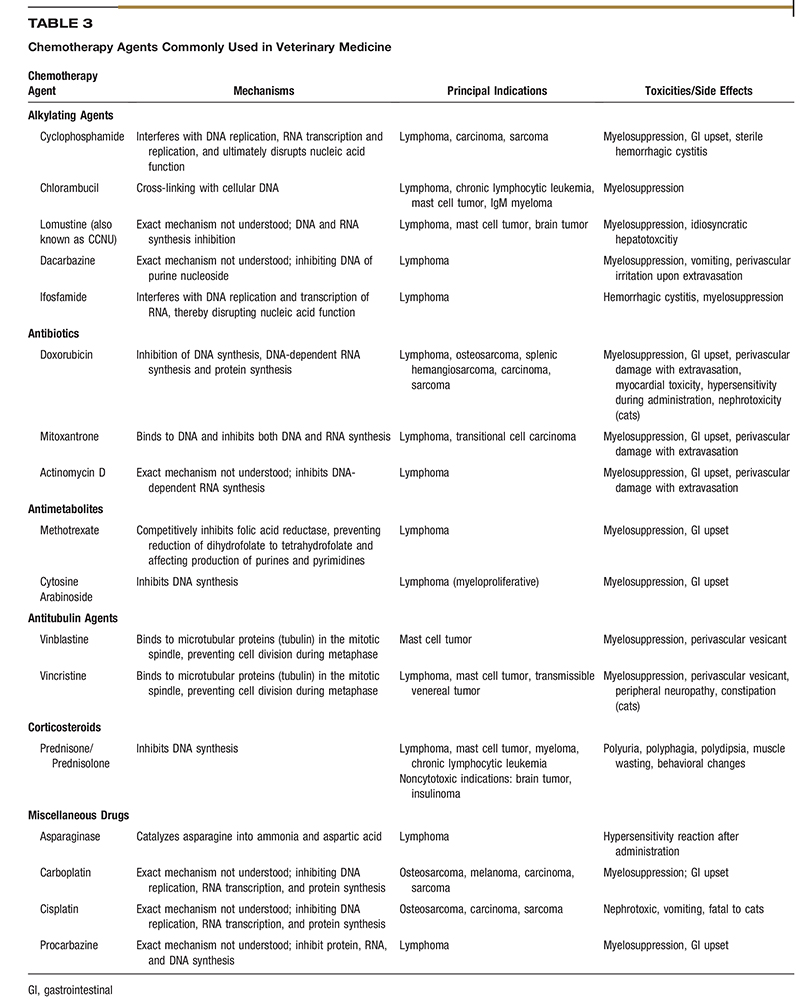

Depending on the tumor type being treated and the stage of disease, MTD chemotherapy may be given alone or as an adjuvant to surgery or radiation therapy. It is indicated for treatment of tumors known to be sensitive to drug therapy, such as hematologic malignancies (lymphoma, multiple myeloma), and for highly metastatic malignancies, such as osteosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, and high-grade mast cell tumors. When conventional chemotherapy is used against solid tumors, such as osteosarcoma, it is often used in an adjuvant setting after primary tumor treatment to slow progression of occult micrometastatic disease. Occasionally, drugs are also given in the neoadjuvant setting to downstage a chemosensitive primary tumor (such as a thymoma or mast cell tumor) prior to definitive surgery or radiation therapy. The two main objectives of conventional chemotherapy are tumor control and maintenance or improvement of the patient’s quality of life. Table 3 lists chemotherapeutic agents with anti-neoplastic activity that are commonly used in veterinary medicine.2

Metronomic Chemotherapy

Metronomic chemotherapy is defined as the uninterrupted administration of low doses of cytotoxic drugs at regular and frequent intervals. Recent studies suggest that this approach may be at least as effective as conventional chemotherapy and is associated with less toxicity and expense.3–5 In contrast to MTD chemotherapy agents that target rapidly dividing tumor cells, the key target of metronomic chemotherapy is tumor angiogenesis. The endothelial cells recruited to support tumor growth are exquisitely sensitive to low and uninterrupted doses of chemotherapy drugs.5 In addition, the genetic stability of endothelial cells makes them inherently less susceptible to the development of drug resistance compared to tumor cells.6 Not surprisingly, metronomic chemotherapy has few adverse effects on non-endothelial cells, such as epithelial cells and leukocytes.

Despite the promise of metronomic chemotherapy, this approach is currently limited by significant gaps in knowledge regarding optimal dosing schedules and drug combinations. The types of cancer best suited to metronomic therapy and appropriate ways to gauge tumor treatment response are also currently unknown. However, there have been several published studies in veterinary medicine, most of which were prospective phase 1 and phase 2 trials that investigated the use of metronomic chemotherapy. The most common neoplasms evaluated in these studies were hemangiosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and transitional cell carcinoma. An assortment of other neoplasms were also evaluated (osteosarcoma, melanoma, and assorted carcinomas) but in a much smaller number of patients.7–11 In the majority of these studies, the oral chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamidea was used.8–10 Other chemotherapeutic agents that have been assessed were lomustine (also known as CCNU) and chlorambucil.7,11 These oral chemotherapeutics were often combined with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) due to the anti-angiogenic properties of the NSAID drug class.5 Due to the generally positive responses reported in these studies, cyclophosphamide has often been used in a metronomic fashion in veterinary medicine, frequently in combination with a NSAID.

In contrast to conventional chemotherapy, the desired endpoint for metronomic chemotherapy is often stabilization of disease rather than an overall reduction in the tumor burden. Metronomic chemotherapeutics are an appealing treatment option for a variety of reasons including reasonable cost, ease of drug administration, and lower toxicity profile when compared to maximum tolerated dose chemotherapy protocols. Most veterinary oncologists offer metronomic chemotherapy when a conventional chemotherapy protocol has failed or has been declined by the patient’s owner. Side effects may occur, but are typically mild and transient. Because sterile hemorrhagic cystitis is a risk with cyclophosphamide chemotherapy administered in either a metronomic or MTD manner, this sequela should be monitored with periodic urinalysis of a voided sample.10 Because other unanticipated toxicities may occur when multiple agents are combined in a protocol, it is imperative that patients be closely monitored.7 Initial metronomic chemotherapy studies have shown positive tumor responses and the protocols are generally well tolerated in veterinary patients.7 While further investigation into the benefits of metronomic chemotherapy in veterinary medicine is needed, this modality is becoming an increasingly popular treatment option.7

Targeted Chemotherapy Using Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Tyrosine kinases are enzymes that are responsible for the activation of proteins involved in the signaling pathways that regulate normal cell proliferation and survival. Because many of these pathways are dysregulated in cancer cells, TKIs are anti-cancer drugs that block signal transduction, thereby preventing tumor growth. There are now two oral TKIs approved for use in dogs with cancer, toceranib phosphateb and masitinib mesylatec (conditionally approved in the United States), which are indicated for the treatment of specific grades and stages of mast cell disease. Although these drugs are targeted to specific signal transduction pathways, each drug can induce toxicities to rapidly dividing normal cells that also rely on these pathways. The most common side effects seen with these chemotherapeutics are gastrointestinal, including diarrhea, loss of appetite, and occasionally vomiting.12,13 Other less common side effects are hepatotoxicity, neutropenia, muscle pain, and coagulopathies. Side effects associated with toceranib phosphateb include protein-losing nephropathy, proteinuria, hypertension, and, rarely, pancreatitis.12 More widespread use of TKIs awaits further investigation of several important questions, such as the tumor types in which TKIs are most likely to be effective and their optimal combination with conventional chemotherapy agents.

Immunotherapy

Capturing the ability of the immune system to fight cancer holds significant promise for the treatment of highly aggressive malignancies, particularly for prevention or control of metastatic disease. The first U.S. Department of Agriculture-licensed immunotherapeutic agent designed for veterinary cancer patients is canine melanoma vaccined a DNA vaccine indicated specifically for dogs with stage II or III oral melanoma in which local disease control has already been obtained. There are a number of other immunotherapies currently being investigated in clinical trials including monoclonal antibodies for dogs with B-cell and T-cell lymphoma and an anti-nerve growth factor antibody that may palliate the pain associated with canine osteosarcoma. As in human clinical trials, the success of immunotherapy for companion animals will likely depend on combination treatment with other treatment modalities, such as radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Therapeutic Modalities: Adjunctive Therapy

Adjunctive therapies have long been used as a means of improving the quality of life in veterinary cancer patients and are now an accepted component of oncology case management. Because the quality of their pet’s life is usually the owner’s first concern, decisions on primary and adjunctive therapies should not only consider disease factors but also the owner’s goals, preferences, and limitations.

A variety of adjunctive therapies are employed in controlling the clinical signs encountered in dogs and cats that are treated for cancer. A treatment goal for any oncology patient is to maintain quality of life by limiting treatment side effects, pain, and discomfort. Clinical signs may be caused by the cancer itself, such as the pain associated with osteosarcoma or may be a side effect associated with a treatment modality, such as radiation or chemotherapy.

Side effects associated with chemotherapeutic agents include vomiting, nausea, anorexia, diarrhea, hair loss, and bone marrow suppression. Although nausea and vomiting are often self-limiting in oncology patients, in some cases they are severe enough to require medical intervention. Fortunately, there are a variety of anti-emetics available today. Metoclopramide has been used for decades in veterinary medicine and is an effective anti-emetic. Maropitant citrate,e a newer NK1 receptor antagonist, is gaining in popularity due to its efficacy and the convenience of oral or injectable once daily dosing. A recent study revealed that the use of maropitant citratee for five days following doxorubicin administration significantly decreased the amount and intensity of vomiting.14 Ondansetron hydrochloridef and dolasetron mesylateg both 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, may also be used to control vomiting. Some advocate the addition of an H2 blocker (famotidine) or proton pump inhibitor (omeprazole) to minimize the risks of vomiting and reflux esophagitis. Diarrhea following chemotherapy administration has also been reported and is often easily managed with metronidazole or opiate antidiarrheals, such as loperamide.

Anorexia attributed to chemotherapy has been reported in oncology patients as well. The most common cause of anorexia is nausea, but occasionally another underlying disease process may be responsible for gastrointestinal signs and should be considered. Appetite stimulants, such as mirtazapine, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, or cyproheptadine, a serotonin antagonist antihistamine, have been used with some success in canine and feline oncology patients. Some veterinarians will dispense medications for owners to have at home and use on an as-needed basis, for example the “3-Ms” of maropitant citratee (or metoclopramide), metronidazole, and mirtazapine. Some clinicians, on the other hand, prescribe medications only at the occurrence of clinical signs. Inmost cases, clinical side effects of chemotherapy are self-limiting or can be managed with owner-administered medications. However, chemotherapy side effects should never be considered trivial. In some cases, they are life threatening and require hospitalization for more intensive treatment.

Nutrition

The nutritional status of all oncology patients should be routinely assessed beginning at diagnosis and throughout treatment. The incidence of cachexia is lowin veterinary patients. It is characterized by a distinct set of metabolic changes that are nearly impossible to reverse once they are present, although dietary modifications can slow progression. Diets should be tailored to each individual taking into account their cancer diagnosis, any other disease processes (e.g., pancreatitis or renal disease), and nutritional needs, as well as environmental factors including other pets in the household and an owner’s ability or willingness to feed the diet. The most important dietary consideration for canine and feline oncology patients is that the ration is palatable and eaten, otherwise it has no benefit. Providing a complete and balanced diet, whether commercially available or homemade, is imperative. A variety of diets have been used for veterinary cancer patientsh,i. Itmay be beneficial to consult a veterinary nutritionist who can formulate a diet specific to the patient.15

Pain Management

Recognition and alleviation of pain in oncology patients is essential for maintaining quality of life. Pain in these patients may be due to the cancer itself, a treatment modality being used (e.g.,radiation or surgery), or a concurrent disease (e.g., osteoarthritis). To adequately control pain, a combination of more than one pain medication (NSAIDs, opioids, and adjuvant drugs such as gabapentin) is routinely required. Practitioners have at their disposal comprehensive sources of information on pain management. Most notably, the recently updated AAHA/AAFP Pain Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats provide current recommendations for a multimodal approach to preempting and controlling pain.16

Therapeutic Modalities: Radiation Therapy

In simple terms, radiation therapy utilizes ionizing radiation to kill cancer cells. The linear accelerator is the standard device for administering radiation therapy, and functions by accelerating electrons at relativistic speeds.17 High-energy photons have excellent penetrability and skin-sparing effect. Electron emissions range in energy from 6–30 megaelectronvolts, have a rapid dosage fall-off, and are useful for superficial tumors where critical structures are located beneath the treated area.

Goals of Radiation Therapy

The goal of definitive or curative radiation therapy is eradication of all viable tumor cells within the patient. Its intent is to cure the patient whenever possible and to prolong survival as long as possible.18 Palliative radiation is playing a larger role in veterinary oncology as owners increasingly seek to improve quality of life, decrease pain, and minimize hospitalization of their pets rather than achieving a cure. Most palliative protocols use lower total radiation doses and a higher dose-per-fraction to accomplish these goals.

Preoperative radiation therapy has potential advantages over postoperative radiation. These include treatment of well oxygenated tissue rather than scars, decreased tumor seeding, a smaller treatment volume, and, in some situations, less aggressive surgery. Potential disadvantages include increased wound complications and delayed surgical extirpation. Preoperative radiation is not used in every situation. The decision to do so is based on tumor location, surgeon preference, and risk of wound complication.

Pet Radiation Therapy Centers

Pet radiology centers are available to veterinarians who wish to refer their oncology patients for radiotherapy. In addition to other resources, the Veterinary Cancer Society provides an online list (vetcancersociety.org) of veterinary radiation therapy centers, including contact information, in 30 states throughout the United States.

Normal Tissue Response

Within the first few wk after the start of radiation, acute effects are typically seen in normal tissues such as bone marrow, epidermis, gastrointestinal cells, and mucosa as well as in neoplastic cells. Factors affecting acute response to radiation in normal tissue include total dose, overall treatment time (dose intensity), and volume of tissue irradiated. Acute effects in healthy tissue are to be expected and will occur if curative doses are administered, but will resolve with time and supportive care. Acute side effects should not be considered dose-limiting although they can temporarily affect the patient’s quality of life. Late effects of radiation are seen in slowly proliferating normal tissue. These effects are related to damage to the vascular and connective (stromal) tissue in non- or slowly-proliferating tissue such as the brain, spinal cord, muscle, bone, kidney, and lung. Damage is often progressive and nonreversible, thus limiting the dose that can be given. Tissue destruction is related to dose, treatment volume, and dose-perfraction, and can be limited through the use of fractionated radiation therapy.

re-Radiation Imaging

Patients with tumors in complex anatomical locations (e.g., head, neck, body wall) may require CT imaging for planning purposes prior to radiation. Patients treated with palliative courses of radiation may not require computer-based planning depending on tumor size and location. Hemoclips placed at surgery aid in delineating the tumor bed.19 Patient positioning during radiotherapy should attempt to exactly duplicate the patient position at the time of CT.

Tumor-Specific Radiation Considerations

A variety of cancers are responsive to radiation therapy. These include brain tumors, nasal tumors, oral tumors, and tumors of the extremities and body. Brain tumor treatment may consist of radiation alone or combined with surgery.20,21 The brain tumors reported to favorably respond to radiation include meningioma, schwannoma, choroid plexus tumors, astrocytoma, glioma, and pituitary macroadenomas and adenocarcinomas. 20,21 All nasal tumors appear to respond to radiation. Specifically, canine and feline lymphoma, sarcomas, and carcinomas of the nasal cavity respond favorably to radiation. Canine oral tumors, specifically acanthomatous epulis, squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma, and melanoma, respond to radiation. Canine soft tissue sarcomas, lymphoma, mast cell tumors, ceruminous gland tumors, thyroid carcinomas, bladder tumors, prostate tumors, perianal adenomas, and apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinomas also respond to radiation, as does localized lymphoma. Radiation is commonly used for palliation in osteosarcomas in dogs.21 Unfortunately, not all cancers respond well to radiation. One such example is a large soft tissue sarcoma.21

Newer Technologies

3-D conformal radiation therapy allows the beam to be tightly shaped to the tumor and allows sparing of normal tissues.22 Intensity modulated radiation therapy allows the beam collimator to move during treatment, allowing the tumor to be irradiated at different angles and distances during a single treatment. State of art radiation therapy currently includes stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic body radiation therapy. These methods involve more sophisticated technology and delivery of single or several fractions of high-dose radiation therapy with a narrow margin. Long-term studies are sparse in veterinary medicine, but these technologies offer the promise of higher doses to tumors, lower doses to normal structures, and fewer dosage fractions.

Therapeutic Modalities: Surgery

As a general rule, if a primary tumor can be completely excised with acceptable morbidity, surgery is the best choice of treatment. The first attempt at surgical excision always offers the best opportunity to completely remove the tumor. Locally recurrent tumors often are more difficult to remove than the initial tumor because of more extensive involvement of normal tissues in the region and distortion of normal tissue planes by scar tissue. For tumors that are large, fixed, or located adjacent to critical normal structures, preoperative CT or MRI may be helpful in planning the surgical excision.

The usual objective of surgery is to obtain wide surgical margins in all directions surrounding the tumor, that is, to remove the tumor with a grossly visible intact cuff of surrounding normal tissue. There is no universally appropriate margin width, and adequate margins vary from tumor to tumor and location to location. Tumors with a high probability of local recurrence (e.g., high-grade soft tissue sarcomas or mast cell tumors and feline mammary carcinomas) should be removed with 2–3 cm margins if possible. Many other malignancies can safely be removed with 1–2 cm margins. The necessary margin often depends in part on the type of tissues that are adjacent to the tumor. For example, fascial planes generally provide a good physical barrier to tumor growth, so that excision of an intact fascial plane below a tumor is an excellent way to optimize the chance of a complete excision. Subcutaneous fat is poorly resistant to tumor growth and should always be aggressively excised with the tumor mass.

A marginal excision refers to “shelling out” a tumor, or excising it just outside its pseudocapsule. Because the pseudocapsule often consists of compressed cancers cells, marginal excisions risk leaving microscopic quantities of tumor cells in the patient and are associated with higher rates of local recurrence than wide excisions. As a general rule, marginal excisions should be avoided unless postoperative radiation therapy is being considered.

All excised tumors should be submitted for histopathologic examination and margin analysis. The accuracy of margin analyses can be optimized by inking the excised specimen to allow the pathologist to distinguish true surgical margins from artifactual margins created during tissue processing. Sutures may be placed in the surface of the excised specimen to guide the pathologist to areas of particular concern. Because pathology labs typically prepare only four or five slides from a given specimen, a report of complete margins does not necessarily imply that an excision was complete. A report of incomplete margins means the resection was histologically incomplete in at least one location. While overall recurrence rates are consistently greater for tumors with incomplete margins than for tumors with complete margins, owners should be aware that tumors with complete margins can recur locally and, conversely, many tumors with incomplete margins do not recur. Following a report of incomplete margins, options include close monitoring (if an appropriate re-excision will be feasible should local recurrence develop), immediate wide excision of the surgical scar, or postoperative radiation therapy.

Follow-Up Care

Assessment of Response

Guidelines have been developed to avoid arbitrary decisions in assessing therapeutic response. Responses must be viewed in context with the original intent of therapy, whether it be cure or palliation. The RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours) model for canine tumors specifies the following response criteria:

- Complete response: 100% resolution of tumor.

- Partial response: >30% reduction in overall tumor(s) size.

- Progressive disease: >20% increase in overall tumor(s) size.

- Stable disease: <30% reduction, <20% increase in tumor(s) size.23

The Lymphoma Response Evaluation Criteria for dogs specifies the following response criteria:

- Complete response: Complete regression of all evidence of disease, normal-size lymph nodes.

- Partial response: >30% reduction in mean longest dimension of lesions.

- Progressive disease: >20% increase in size in mean longest dimension of lesions.

- Stable disease: <30% reduction, <20% increase in size of lesions.24

Post-Radiation Therapy Monitoring

Many patients have a good-to-excellent prognosis following initial radiotherapy. However, it is imperative for these patients to have periodic post-therapy examinations due to the possibility of recurrence, metastasis, new tumor development, or complications of initial therapy. Upon completion of initial therapy, patients are often restaged to determine extent of disease. Some tumors can take mo for the maximum treatment response to occur, so patience and ongoing supportive care is advisable. Partial response or stabilization of the growth of the primary tumor, leaving residual disease, may be the maximum post-therapy response seen.

Maintenance Chemotherapy

For many oncology cases, initial therapy is done to prolong survival even though it is not considered curative. Additional chemotherapy, metronomic chemotherapy, or TKIs and cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors (COX-2) have been used as ongoing therapy in such cases. Use of the latter two agents is justified by their antiangiogenic properties as well as their anti-proliferative effects.25,26

Management of Recurrent or Metastatic Disease

The concepts that apply to maintenance chemotherapy are relevant to managing recurrent or metastatic disease. Pet owners should be prepared for repeat imaging and staging prior to final treatment decisions. Assessment of the patient’s quality of life is needed at this critical juncture because of the guarded prognosis and likelihood that a return to normalcy may not be possible. Goals of therapy in such cases are often dynamic and are obviously impacted by extent of disease and expectations for the patient’s quality of life.

Overview of Common Cancers

Tables 1 and 2 are designed to facilitate initial conversations between practitioners and owners about some of the most common cancers seen in dogs and cats. The tables are intended as a quick reference and do not fully capture the variability in the behavior of the tumors listed, cannot be used to predict outcome in individual patients, and are not intended to serve as a primary resource for making clinical decisions.

Case Study: Canine Osteosarcoma

FIGURE 1

Radiographic view of the right front limb of a dog with no visible swelling and grade 2 lameness reveals a proliferative, osteolytic lesion of the distal

radius. (Image courtesy of Laura Garrett.)

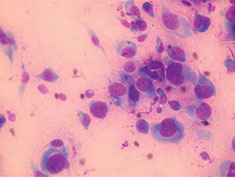

FIGURE 2

A cytology specimen obtained from a suspected tumor site reveals a cellular architecture indicative of sarcoma, including indistinct cytoplasmic borders and

atypical nuclei. Fine-needle aspiration in this case enabled a confident sarcoma diagnosis without resorting to a more invasive biopsy technique. (Image courtesy of Laura Garrett.)

The case study presented here is an example of how diagnostics and therapeutics can be used in the management of a cancer patient. The case study is not intended be prescriptive or to imply that the approach taken here is the only way to manage an osteosarcoma patient, nor is it intended to be used as a diagnostic tree. Practitioners interested in oncology are encouraged to research current diagnostics, chemotherapeutics, and modalities appropriate for each cancer patient as the best way of keeping current in this rapidly evolving field of veterinary medicine. The case history includes the rationale for “decision points,” the interventions the clinician would make in appropriately treating the patient.

A 9 yr old, male, neutered Labrador retriever mixed-breed named “Bo” presented with a 2 mo history of mild lameness in the right front limb. The dog was an outside farm dog from rural Tennessee. Bo had been seen by another veterinarian 1 mo previously and was treated with a NSAID for 2 wk. The owners had not seen an improvement.

On physical exam, Bo had a body condition score of 4/9. He had a grade 2/4 lameness in the right front limb and was mildly painful over the right carpus with no visible swelling. Distal limb radiographs revealed an osteolytic and proliferative lesion of the distal carpus (Figure 1). The lesion did not cross the joint. Threeview thoracic radiographs revealed no visible lesions and were considered normal.

Decision point rationale: Approximately 8% of dogs with osteosarcoma have visible metastasis on radiographs at diagnosis. Other diseases on the differential list are a metastatic bone tumor and infectious disease (bacterial, fungal). These considerations were discussed with the owner and a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the lesion was recommended.

Decision point rationale: A FNA is often diagnostic and is less invasive than a bone biopsy. If the cytology is consistent with sarcoma, an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) stain may be used to confirm bony origin. A percentage of cartilage tumors will also be ALP-positive.

Cytology of the FNA confirmed sarcoma and an ALP stain was positive (Figure 2). Based on these findings, the physical exam, and the patient’s history, a diagnosis of OSA was made.

The patient’s prognosis and treatment options were discussed in detail with the owner. Treatment of the local disease (primary tumor) and systemic disease (micrometastasis) was discussed. Treatment options included surgery (amputation or limb sparing), surgery with chemotherapy, referral for these procedures, referral for definitive radiation therapy, and palliative care. Palliative care included pain management or referral for palliative radiation.

Decision point rationale: If a referral is made, follow-up care by the primary care veterinarian is appropriate. Therefore, it is important that the primary and referral veterinarians discuss postoperative care, follow-up blood work, and management of any potential side effects.

The owner elected to pursue further staging diagnostics and was considering amputation with follow-up chemotherapy. A complete blood count, comprehensive chemistry profile, and a urinalysis were performed to rule out comorbidities. Elevated serum ALP is a negative prognostic indicator. Additional staging considerations would entail referral for a bone scan to identify other bone lesions (<10% of cases have detectable bone metastases) and abdominal ultrasound (<10% of dogs have intra-abdominal metastases). Results of the blood work and urinalysis were normal.

A forelimb amputation was performed and recovery was uneventful. At the time of suture removal, carboplatin chemotherapy was initiated and given IV once every 3 wk for a total of four treatments. Decision point rationale: There are multiple chemotherapeutic treatment options for osteosarcoma. Chemotherapeutic agents with proven efficacy include doxorubicin, cisplatin, and carboplatin. However, studies generally have not shown clear differences in outcome between the various protocols.

Bo returned to normal activity. His quality of life improved after amputation of the forelimb and alleviation of pain. He tolerated his chemotherapy well, but required a few days of antiemetics after two of the treatments.

Three-view thoracic radiographs were performed every 3 mo following completion of chemotherapy. Nine mo after the last chemotherapy treatment, radiographic evidence of metastasis was found. Bo was normal clinically and enjoyed a good quality of life.

The primary care veterinarian discussed Bo’s prognosis with the owner, including the likely terminal nature of the metastatic OSA and scenarios for the patient’s quality of life. Because Bo currently had a good quality of life, the owners opted to begin therapy for the metastasis. Bo was placed on a TKI for the management of his metastatic disease.27

Decision point rationale: Cancer should be considered and treated as a chronic disease much like end-stage renal disease or heart failure. Once metastatic disease becomes clinically apparent, a realistic goal of therapy is to attempt to stabilize it or slow its progression. Metronomic chemotherapy and TKIs are both excellent considerations in this scenario. For most owners, maintaining a good quality of life is the most important consideration.

Three mo later, three-view thoracic radiographs revealed that Bo’s metastatic disease had not progressed and was stable. Bo continued to maintain a good quality of life for 6 mo until he eventually became dyspneic. Advanced metastatic disease was documented radiographically, and the owners elected euthanasia.

Safety Considerations for Personnel, Patients, Pet Owners, and the Environment

The importance of attention to appropriate safety precautions in handling hazardous drug (HD) preparations in the clinic setting cannot be overemphasized. The veterinarian is legally and ethically obligated to educate staff regarding safe handling of chemotherapeutic drugs. Lack of staff communication and training in chemotherapy protocols could lead to an Occupational Safety and Health Administration investigation, fines, and lawsuits. Staff should have access to relevant Material Safety Data Sheets and be made aware of the toxicity of any chemotherapeutic agent that is used in the practice.

For the purposes of these guidelines, HDs will be used interchangeably with chemotherapeutic agents. A complete list of HDs has been compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).28 Improper handling can lead to unintended exposure to cytotoxic agents that are mutagenic, teratogenic, or carcinogenic. For example, exposure of healthcare workers to HDs has been confirmed by the presence of HD metabolites in urine.29 For this reason, safety is a paramount consideration for everyone involved with chemotherapy.

Personnel Safety Considerations

There are several routes of exposure to HDs. HDs can enter the body via inhalation, accidental injection, ingestion of contaminated foodstuffs, hand-to-oral contact, and dermal absorption.30 While HD exposure is always a constant threat when chemotherapeutic agents are used, proper procedures and policies can minimize the risk. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) has developed an enforceable “General Chapter” practice standard devoted to the handling of HDs, which outlines standards regarding personnel protection for preparation and handling of HDs. Because an indepth discussion of HD controls is beyond the scope of these guidelines, readers can refer to USP for more detailed information on this topic.

Veterinary practices will ordinarily not be involved in chemotherapeutic drug compounding. However, it is helpful for the healthcare team personnel to have a general awareness that direct contact with HDs, either by handling, reconstituting, or administering HDs, represents an exposure risk.31 Many HDs have also been found to have drug residue on the outside of drug containers, which creates another opportunity for exposure of individuals who receive drugs and perform inventory control procedures.32 Personal protective equipment (PPE) should be used to protect personnel from exposure during handling of HDs. PPE includes gloves, gowns, goggles for eye protection, full face shield for head protection, and respiratory barrier protection.

Regular exam gloves are not recommended for use as standard protocol for handling chemotherapeutic agents. However, as an expedient, wearing two pairs of powder-free nitrile or latex gloves can be used as a last resort. Vinyl gloves do not provide protection against chemotherapy. Ideally, gloves should be powder free and rated for chemotherapy use by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). For receiving HDs, one pair of ASTMtested chemotherapy gloves may be worn.31 When administering, managing, and disposing of HDs, two pairs of ASTM-tested chemotherapy gloves may be worn.31 The inner glove should be worn under the gown cuff and the outer glove over the cuff. Disposable gowns made of polyethylene-coated polypropylene or other laminate materials offer the best protection.31

Eye, face, and respiratory protection is mandatory when working with HDs outside of a clean room or isolator cabinet, or whenever there is a probability of splashing or uncontrolled aerosolization of HDs. A full face mask is a suitable alternative to goggles, although it does not form a seal or fully protect the eyes. A NIOSH N95 respirator mask is suitable for most situations, with the exception of large spills that cannot be contained by a commercially available spill kit.

PPE should be removed in the following order: chemotherapy gown (touching the outside of the gown, then rolling the outside inward to contain HD trace contamination), goggles and face shields (touching only the outside without making contact with the face), then chemotherapy gloves (touching the outside of the gloves away from the exposed skin while attempting to roll the glove outside-in). If a glove becomes contaminated or if there is a breach in the glove, it should be removed and discarded promptly, while carefully avoiding contamination of the handler’s skin or nearby surfaces.

Closed system transfer devices (CSTDs) are another type of PPE that can be used for any cytotoxic chemotherapy agent (although not necessarily for all HDs) during preparation and administration. In the case of non-cytotoxic agents that are not on the NIOSH list of HDs, for example, asparaginasej, a CSTD is not required. FDA approval of CSTDs requires the following capabilities: no escape of HDs or vapor, no transfer of environmental contaminants, and the ability to block microbial ingress. CSTDs can greatly reduce the potential for HD exposure to clinical personnel and should always be used concurrently with other PPE.

Traditional needle and syringe techniques for mixing HDs create the potential for droplet or aerosol contamination with the drugs that are being handled. CSTDs prevent mechanical transfer of external contaminants and prevent harmful aerosols that are created from HDs mixing from escaping and exposing personnel.30 CSTDs are commercially available from a number of companies k,l,m,n.

The following additional safety precautions will help minimize the potential for exposure of personnel handling HDs:

- Male and female employees who are immune-compromised or attempting to conceive, and women who are pregnant or breast feeding, should avoid working with chemotherapy agents.

- Employees or pet owners who will be exposed to the patient’s waste (urine, feces, vomit, blood) within 72 hr of chemotherapy administration (sometimes longer for some drugs) should wear proper PPE.

- Chemotherapy pills (tablets and capsules) are best handled within a biological safety cabinet (BSC) if available. If no BSC is available, a ventilated area or a respirator should be used to avoid inhalation of HD particles or aerosols.

- Separate pill counters should be used for chemotherapy pills. Counters labeled for chemotherapy use will help avoid inadvertent use with conventional medications. The counters should be stored either within the BSC (not to be removed) or in a sealed container (i.e., a plastic box with secure lid) dedicated to that pill counter and any other items that may come in contact with HD pills.

Environmental Safety Considerations

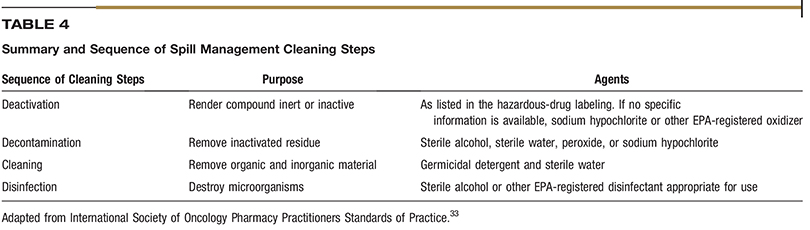

Environmental controls are an important part of risk mitigation. The recommended location for chemotherapy preparation and administration is a quiet, low-traffic room that is dedicated to chemotherapy purposes, free from distractions, and easy to clean. Because HD spill events represent the greatest risk of personnel exposure, it is important to use extreme care when cleaning spills. Commercially available spill kits are useful in containing and cleaning HD spills. Absorbent pads or pillows can be used to immediately contain larger spills. When managing a spill, it is recommended to start from the outer edges of the spill and work your way towards the middle to prevent spreading HD residue. A HD-spill management sequence (Table 4) has been developed and is a suitable basis for a veterinary practice protocol.33 Spill kits should contain instructions for use and be located in areas where HDs are located and administered. Only trained personnel should cleanup HD spills and should be wearing appropriate PPE, including double chemotherapy gloves and respiratory masks.

HD agents are best stored in a dedicated, closeable cabinet or refrigerator. Following administration, discard HDs, administration materials, and gloves and other PPE into chemotherapy waste receptacles. It is important that staff members who have touched chemotherapy vials or potentially contaminated areas NOT touch anything or anyone else until they have removed their PPE and washed their hands.

Patient Safety Considerations

Chemotherapeutic agents have a narrow therapeutic index and can lead to significant or fatal toxicity if overdosed. Errors in dose calculations and labeling as well as breed-specific sensitivities can lead to adverse events. Errors in dose calculations are responsible for a large portion of mistakes made in chemotherapy. In veterinary medicine, agents may be dosed in terms of milligrams/ kilogram (mg/kg) or milligrams per meter squared (mg/m2). These are easily confused and can lead to drastically different dose calculations. Prior to mixing chemotherapy drugs, calculations should be done by two individuals. The two calculated doses can then be compared and serve as a double check. The concentration of drug in mg/ml should also be double-checked.

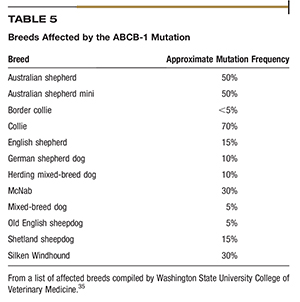

The Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine has extensively investigated the ABCB-1 gene (formerly known as MDR1), which is responsible for breed-specific variability in susceptibility to adverse events. The ABCB-1 gene codes for the production of p-glycoprotein (Pgp) pumps, which act to remove drugs from individual cells.34,35 The Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine has published a list of breeds that have a high probability of an ABCB-1 gene mutation (Table 5). Many chemotherapy drugs, notably vincristine and vinblastine, are substrates for p-glycoprotein (Pgp) pumps and require a dose adjustment for that reason.34

When administering chemotherapy to an animal, proper restraint is very important in order to prevent drug extravasation. Staff members assisting with restraint should wear chemotherapy gloves and other appropriate PPE. Frequent monitoring of the injection site should be performed throughout the injection or infusion. Placement of a small-gauge IV catheter (e.g., 24 g, 22 g) will preserve vein viability and provide secure access. Although winged infusion sets are not as secure as IV catheters, they can be used for bolus injections of drugs such as vinca alkaloids, cyclophosphamide, and carboplatin. Winged infusion sets should never be used for severe vesicants, such as doxorubicin, or for lengthy infusions.

Venipuncture should entail a nicely seated, one-stick technique in order to avoid creating multiple holes within the vein wall that would allow the chemotherapy drug to leak into surrounding tissue. After chemotherapy administration is complete, apply gauze or alcohol swab to the injection site when removing the needle or catheter from the patient. This can help stabilize sudden movements of the exiting cannula as well as absorb possible residual chemotherapeutic agents contained within.

Because heparin can cause precipitation or inactivation of some chemotherapy agents, non-heparinized flushes are recommended. A 0.9% NaCl preparation is a standard fluid choice. Prime any lines with the 0.9% NaCl or other fluid prior to the addition or administration of chemotherapy.

Extravasations

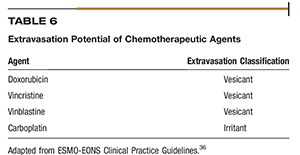

Extravasation is the process of liquid leaking into surrounding tissue, typically near the insertion site of a peripheral catheter. Drugs are classified according to their potential for causing damage as vesicant, irritant, or a nonvesicant.36 Table 6 lists the extravasation potential for five injectable chemotherapies used in veterinary medicine.36

Most extravasation events can be prevented by a systematic, standardized, evidence-based approach to administration techniques. A trained and experienced staff will greatly decrease procedure-related extravasation risk factors. Fidalgo et al. outline a preventative protocol that may help minimize the risk of extravasations.36

The most common signs of extravasation are discomfort, pain, swelling, and redness at the injection site. Prolonged symptoms often progress to tissue ulcerations, blistering, and necrosis. Indications of an extravasation event include the absence of blood return from the catheter, bolus administration resistance, and failure of the infusion. If an extravasation event does occur, do not immediately remove the catheter. Rather, attempt to aspirate as much drug as possible and do not inject any fluid into the catheter. An extravasation mitigation protocol should be implemented as soon as possible.36

Labeling of Hazardous Drugs

Labeling of HDs is an extremely important aspect of personnel safety. Without adequate HD labeling, personnel are placed at risk of accidental exposure to HDs. All HDs should be labeled clearly with chemotherapy warning labels. Injectable HD agents should be labeled as “opened” or “reconstituted” on a specific date and the concentration of the reconstituted agent should be indicated.

“Look-alike, sound-alike” describes drugs that are spelled and pronounced similarly but are different. The term came about in response to errors involving inadvertent misfills of drugs, for example, vincristine being confused with vinblastine. A simple practice that many pharmacies now follow is arranging their medication stock alphabetically by generic name using a “Tall Man Lettering System.”37 This is a simple way to emphasize spelling and pronunciation differences between drugs (e.g., vincristine is written as vinCRIStine and vinblastine is written as vinBLAStine.)37

Appropriate labeling of mixed chemotherapies can also reduce errors and allow for another double check prior to administration. Diluted drugs should be labeled with the amount of drug in milligrams contained in the syringe or minibag. For drugs that are not diluted, it is good practice to label the syringe with the concentration of the drug as it comes from the vial. These labeling techniques allow for another double check prior to administration.

The Institute for Safe Medical Practices has developed several strategies to prevent simple errors. Naked decimal points and trailing zeros have been implicated in many errors in healthcare and have been designated as unapproved abbreviations.38 An example of a naked decimal point is when “0.2 mg” is written as “.2 mg,” easily leading to a 10-fold overdose if “.2 mg” is read as “2 mg.” Similarly, a trailing zero notation is when “10 mg” is written as “10.0 mg,” which can easily be mistaken for “100 mg.”

Client Support and Communication

Good communication skills are a key component of a successful practice.39 Oncology cases raise the bar by placing a premium on the clinician’s ability to engage and empathize with the owner of a cancer patient. Cancer is an upsetting diagnosis associated with emotionally charged situations. The goal of the initial discussion is to present detailed information about the diagnosis, testing and treatment options, and prognosis while at the same time assessing the client’s goals and limitations, all done in an empathetic and supportive manner. Understanding costs, risks, benefits, and potential outcomes is crucial for owners of pets with cancer, as is feeling part of a caring team battling the disease. Multiple studies in human oncology confirm that effective communication skills are a critical source of satisfactory case outcome for both the patient and clinician.40–42

Nonverbal Communication

A large part of communication between individuals is nonverbal and often unintentional. Unspoken information that cannot be hidden is still being exchanged at all times. The nonverbal aspects of communication can give away what a client may be thinking or feeling, possibly contrary to what they say. Hesitantly saying, “yes” and looking downwhen asked, “Do you understand?” is a non-verbal “no” fromthe client. Frankly addressing issues when nonverbal cues indicate lack of understanding or acceptance will save future misunderstanding and upset. Practitioners should be mindful of their own nonverbal “body language” as well as that projected by their clients.

Empathy

Empathy is the ability to imagine what a client is experiencing and to reflect that understanding. Stated another way, empathy can be thought of as having a client know that he or she is being seen, heard, and accepted. ‘You seem worried” or ‘you look like you have some questions” are statements that show clients that they are recognized as individuals with feelings and emotions, and not just as a customer. While statements like these might seem awkward or unnatural at first, the ability to express empathy improves with practice. A common concern is that acknowledging a client’s concerns or state of mind will escalate that person’s emotions. Experts agree that the opposite usually occurs. Acknowledging their distress, discomfort, or doubts helps clients know that their feelings are seen and accepted. This usually helps the client focus on the medical discussion and treatment issues. Examples of nonverbal displays of empathy include varying your speaking tone and rate, adopting a sympathetic posture, or simply handing a box of tissues to a crying client.

To clients, knowing that they are being heard is as powerful as knowing they are seen and recognized. Telling clients that you recognize their concerns uses a core communication skill: reflective listening (discussed in more detail later). This type of acceptance will help the owner of a cancer patient to be open and express difficult or even embarrassing issues and questions. Statements like ‘I can see that this is difficult to discuss” or ‘it is common for these masses to be overlooked until they become large” can be reassuring to the client and open lines of discussion.

Open-End Versus Closed-End Questions

Posing open-end questions is a simple but particularly useful technique for obtaining an accurate patient history and having fruitful discussions about diagnostic results and treatment choices. Open-end questions tend to strengthen the client–veterinarian relationship by allowing pet owners to tell their story. When that occurs, clients feel that their comments and opinions are valued and are contributing to the veterinarian’s understanding of the situation.

Open-end questions often begin with the words “what” or “how” and allow the client to talk using their own vocabulary. An open-end question is a good way to begin an interview, such as, “What has been going on?” Open-end questions are also useful as the case progresses because they encourage the client to make difficult but unavoidable decisions. The skill and sensitivity with which these questions are posed is important. For example, asking a client “Are you thinking about euthanasia?” risks an emotional response. A better approach would be to ask, “What are your thoughts about the options we have discussed?” A good guideline is to ask first and then tell. When a new diagnosis has been made, asking a client what they know about the disease rather than offering a description of the problem can save time and show the client that they, and their knowledge, are valued.

Reflective Listening

Reflective listening involves repeating or paraphrasing what another person has said or implied. This technique is a good way of showing empathy and is an excellent tool for ensuring that you understand the client’s viewpoint. Reflective statements not only tell clients they are being heard but also allow them to correct misconceptions. In that sense, reflective-listening comments operate as a kind of check step in how you perceive the case and the client’s point of view. The classic reflective listening response begins with the phrase, “What I hear you saying is …” Other phrases that may feel more natural or less clichéd are “so, you are saying” or “it sounds like …” For example, a comment like “It sounds like you may be concerned about the cost” may elicit a response like, “Yes, it seems expensive” or “No, cost isn’t the problem, it’s the time involved.” When the reflective-listening approach to dialogue is used, a client’s true feelings and opinions often emerge because you are asking them to confirm or modify your understanding of what they have said.

Breaking the News

Clients need time to adjust to the idea that their pet may have cancer, particularly if the prognosis is poor. Being empathetic and candid in discussing a suspected or confirmed cancer diagnosis often helps the pet owner accept the situation and make treatment decisions in coherent, proactive manner. It is a good idea to announce a cancer diagnosis with a “warning shot” phrase, such as, “I’m afraid the news is not good.” Using short phrases and waiting for the client’s response is a good approach to discussing a cancer case. An example would be, “I’m so sorry about this upsetting diagnosis. Lymphoma is a common cancer in dogs. Unfortunately, it’s not curable but the good news is that it is treatable.” Then pause and ask, “Would you like to discuss further testing and treatment now, or would you prefer to talk later?”

Most clients will have a negative response to the words “cancer” and “chemotherapy.” Their initial reaction to a cancer diagnosis often changes as they process and accept the difficult news and listen to the options on how to proceed. It is not uncommon for an initial refusal to consider more testing or treatment to change with further discussion about how well most pets do with their therapy. The likelihood of that change of heart occurring often depends on the extent to which the veterinarian applies the core communication skills of nonverbal communication, empathy, open-end questioning, and reflective listening. A practitioner who takes that approach almost always helps the pet owner transition from shock and sadness over a cancer diagnosis to taking an active role in managing their pet’s disease.

Offering Options

When discussing a cancer diagnosis or treatment plan with a pet owner, it is important to use lay terminology or medical vocabulary accompanied by a clear explanation. Using clinical terminology that clients are unfamiliar with will only create confusion or embarrassment and add to the owner’s sense of being overwhelmed. When presenting treatment options, it is important to avoid overwhelming the owner with choices and unnecessary detail. First assessing the client’s goals and limitations is an integral part of presenting options. When suggesting that the patient’s prognosis is poor, keep in mind that only the pet owner can determine the value of the additional time treatment may provide. Clients should be advised that median survival time does not predict what the outcome will be for an individual patient. Balancing realism with optimism is critical for veterinarians treating cancer.

Applying the core communication skills discussed here will help a client to view the veterinarian as a partner-in-care when facing a pet’s cancer diagnosis. Together, the healthcare team can make decisions and implement a treatment plan that proves satisfactory for all concerned.

End-of-Life Decisions

One of the options that veterinary medicine has to offer in order to alleviate pain and suffering is euthanasia. Many cancer cases will conclude with a discussion and an end-of-life decision involving the owner and a member of the healthcare team. Understandably, these discussions can be difficult. Practitioners should be prepared to help the pet owner realize that euthanasia is a humane alternative and a viable option to end a pet’s suffering or an unacceptably poor quality of life. Veterinarians should advise clients to consider euthanasia when the clinician can no longer prevent suffering, preserve the pet’s quality of life, or otherwise ensure the quality of its death. In cases where euthanasia is advisable, the veterinarian should consider offering the owner the option of being present during the procedure and spending as much time as they wish with the pet immediately prior to euthanasia. Many practices now have a designated room that provides privacy and a non-clinical, stress-free atmosphere for the euthanasia procedure. A bereavement counselor and support groups can be great resources for the client at any point before or after a pet’s passing.

Optimizing the Contributions of the Entire Practice Team

It is important to enlist the skills and resources of the entire healthcare team when caring for an oncology patient. Good communication and understanding of the practice’s oncology protocols within the team allow each member to provide the client with consistent information on the patient’s status, treatment plan, and outcomes. By “speaking with one voice,” the practice minimizes the potential for confusion and disillusionment by the client when an often sensitive oncology case is involved. An informed, empathetic team approach to presenting information empowers the client to make an educated decision on treatment options and helps create realistic expectations for treatment outcome, quality of life, and life expectancy.

The Critical Role of Staff Training

The entire healthcare team can contribute in a unified fashion to managing an oncology patient and supporting its owner. To accomplish this, a thoughtful approach must be taken to defining the roles and responsibilities of each staff member involved in an oncology case. Equally important, if not more so, is to conduct training to ensure that all staff members understand their responsibilities in such cases and have the skills and knowledge to carry them out. In particular, staff training is most effective when it addresses empathetic interaction with pet owners and safe handling of chemotherapy drugs. An expectation that all staff members will effectively contribute to oncology case management is not realistic unless they have been trained to do so. Practices should assess their training programs to ensure that the unique requirements of oncology treatment are specifically addressed. Useful recommendations for engaging and training the entire healthcare team to implement clinical protocols are provided in recently published feline healthcare guidelines.43

Challenges and Fulfillment for the Healthcare Team

Cancer treatment can be emotionally difficult for all concerned. For example, “compassion fatigue” is a phenomenon characterized by a gradual decline in interest and empathy toward individuals experiencing hardship. Compassion fatigue is real and can negatively impact the quality of care. Body language that conveys impatience, superficial interest, or false sincerity is readily perceived by the client. A team approach to oncology case management is an excellent way to combat compassion fatigue affecting an individual member. When each member of the team supports and complements each other, compassion fatigue is less likely to occur in the first place and other negative behavior patterns can be detected and discussed among the staff.

The opportunity to demonstrate compassionate care and possibly extend the life of a valued pet while offering empathy for its owner can make oncology cases some of the most fulfilling a veterinarian and the entire practice team will encounter. Treatment of a cancer patient is especially rewarding when the outcome is remission or cure, improved quality of life, or longer lifespan for the patient. Even in cases where a favorable outcome does not occur, the experience can still leave the client with a positive impression of the practice. This occurs when the healthcare team is perceived as united in its commitment to the patient’s welfare and genuinely concerned about the relationship between the pet and its owner.

Summary

Every primary-care companion animal practice will encounter canine and feline oncology cases. A successful, full-service practice should be prepared to diagnose, stage, and treat cancer in dogs and cats, and should have a relationship with veterinary oncology specialists for purposes of selective case referrals. Cancer cases are often among the most sensitive and challenging that a practitioner will encounter. Few areas of expertise can do more to strengthen a practice’s relationship with its clients than having an effective protocol and approach to managing cancer in canine and feline patients.

Cancer treatment is case specific and multifactorial. Treatment modalities are based on the tumor type and its stage. Staging is a critical factor in deciding which treatment modalities to use, or whether to treat the disease at all or to instead rely on palliative measures. Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, adjunctive therapies, radiotherapy, and surgery can be used individually or in tandem depending on the type of cancer involved and the owner’s preferences. Chemotherapy is now commonly used in veterinary oncology. However, the inherent toxicity of chemotherapy agents requires strict safety precautions to avoid inadvertent exposure of the patient, clinical personnel, the pet owner, and the environment.